Influence Wars: At the Heart of the Wagner Nebula

By: Said Panda

The figures surrounding the Russian mercenary organization Wagner are highly uncertain due to the opaque nature of its activities. However, the revenues generated by Wagner over the past decade are estimated to range from several hundred million to a few billion dollars, according to various sources. Despite this uncertainty, it is possible to establish a somewhat exhaustive overview of the organization’s operations.

Once considered a mere temp agency for adventurers with no scruples, ready to take up arms for a handful of cash, Wagner is now regarded by all security and influence warfare experts as Moscow’s official proxy for missions that Russia cannot or does not want to officially undertake.

From Ukraine to the Sahel, through Syria, Libya, Sudan, and the Central African Republic (CAR), Wagner’s portfolio is as diverse and eclectic as that of a hired assassin. The common thread between these conflicts where the Russian organization has intervened is Moscow’s direct or indirect involvement. While it may initially seem like Wagner’s sole objective is to maximize financial gain, questions of influence are never far behind. Wagner plays its role as Russia’s proxy with exceptional precision, executing missions with finesse.

In the Beginning, There Was Prigozhin?

The founder of Wagner, Yevgeny Prigozhin, is a former convict. Some even argue that he has never stopped being a criminal, equating his role as head of a mercenary company to a way of legitimizing illegal, even mafia-like activities.

In 1981, at the age of 20, Yevgeny Prigozhin was a notorious delinquent, well-known to the police in his hometown of St. Petersburg, which is also the birthplace of President Putin. He served several prison sentences for various crimes: armed robbery, fraud, extortion, among others.

In the underworld of St. Petersburg’s organized crime scene, it was said that one should avoid crossing paths with Prigozhin. With his imposing stature and a face reminiscent of a gangster from crime films, the young Yevgeny served as muscle for local mafia bosses, carrying out their dirty work.

Influence Wars: At the Heart of the Wagner Network

In 1990, Yevgeny Prigozhin was released from prison after serving ten years behind bars. During his incarceration, he learned to cook, a skill offered to inmates as part of their reintegration training. It turned out he had a real talent for it. Upon his release, he opened his first restaurant, New Island, which quickly became one of the most popular dining spots in St. Petersburg. Hardworking and inventive, he seemed to have found his calling. The restaurant’s reputation grew to the point that Vladimir Putin, a regular customer, frequented the establishment. When Putin rose to power in 1999, he naturally opened the Kremlin’s doors to Prigozhin, who was often invited to showcase his culinary skills at special events. This earned him the nickname “Putin’s chef,” though he never formally served as the Kremlin’s head chef.

The Birth of Wagner

Prigozhin leveraged his proximity to Russia’s new strongman to tap into lucrative markets. He secured contracts to manage military barracks’ cafeterias and cater for operational units. This connection offered him two significant advantages: he became familiar with the military and built relationships with officers who would later help him establish Wagner in 2014. These military contracts also brought him enormous wealth. The former convict became very rich. In a 2018 article, Sergey Sukhankin, a recognized expert on Russian affairs, estimated that Prigozhin had invested up to $120 million (around 74 billion CFA francs) into Wagner.

Prigozhin never publicly explained how the group got the name Wagner. However, some sources claim it was named after the nom de guerre of its actual creator, Dmitry Utkin, while Prigozhin was initially just the financier. Utkin, a former Russian special forces officer, reportedly had a fascination with Richard Wagner, Adolf Hitler’s favorite composer.

Media and the War of Information

Media and disinformation are key pillars of Russian influence. Many African states, often criticized by Western powers and international institutions, seek respect and acknowledgment. African populations increasingly feel that their leaders are treated condescendingly by Westerners, as if they were mere puppets. Statements by figures like Emmanuel Macron, perceived as arrogant or paternalistic toward African leaders, are just a softer illustration of what irritates Africa in its relationship with the West. Sensing this discontent, Moscow has capitalized on the opportunity, needing only to exploit doors already opened by Western arrogance.

For over a decade, anti-French and, more broadly, anti-Western messages have flooded the internet, targeting African audiences. As intelligence documents from a European country reveal, “Many Africans, harboring unresolved colonial grievances against former powers, amplify Russian propaganda without moderation or scrutiny, spreading anti-French rhetoric through social media.”

In the Central African Republic (CAR) and the Sahel, where France intervened to combat armed groups and extremists, years of involvement have led to stagnation. Russian propaganda, disseminated through Wagner, offers a simplistic narrative: if France fails to resolve these conflicts, it’s because it finances and arms rebels in CAR and jihadists in the Sahel. As implausible as this may seem, this false narrative convinces many Africans, who are drawn to rumors. Traumatically fatigued by unending asymmetric wars with civilian and military casualties, populations in places like CAR and the Sahel turn against the French military they once welcomed as saviors. Without firing a single shot, Russia has managed to push France out of its traditional sphere of influence through nothing more than disinformation—a phenomenon now called “influence warfare.”

Influence Warfare: Controlling Information Wins Wars

Wagner is, in reality, a generic name. Legally and formally, it refers to Concord Management Consulting, headquartered in St. Petersburg. This parent company oversees all of Prigozhin’s group activities, which span food services (the source of his wealth through Concord Catering for the Russian military), security, and influence operations like propaganda and disinformation. Once shrouded in total secrecy, the mercenary group inaugurated its headquarters in a St. Petersburg skyscraper on November 4, 2022.

While Wagner is visible through its mercenary operations, influence remains a fundamental yet clandestine activity of Prigozhin’s group. By injecting false information into the collective consciousness of targeted populations, they ensure these beliefs persist indefinitely. This aspect is managed by Patriot, a subsidiary of Concord. Patriot operates through two agencies: the Internet Research Agency (IRA) and RIA FAN.

From their St. Petersburg headquarters, Yaroslav Ignatovsy and Igor Osadchy oversee IRA, running troll factories with astonishing efficiency. In 2016, the United States accused IRA of being “a producer of fake information that destabilizes societies through fake social media accounts.” Experts have since demonstrated Russia’s involvement in repeated online attacks against Hillary Clinton, which likely influenced American voters to favor Donald Trump, seen by the Kremlin as less hostile. On November 7, 2022, Prigozhin publicly admitted to orchestrating operations to prevent Hillary Clinton’s election.

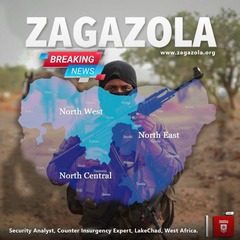

Africa: A Market for Russian Fake News

For years, Russian trolls have targeted African audiences, turning them into a lucrative market for fake news. African public opinion often reacts exactly as the propagandists intend. Anti-French protests have frequently preceded demands for French military withdrawal from Sahelian countries.

In December 2021, Senegalese opposition supporters attacked French businesses like supermarkets and gas stations, even though France had no involvement in the political disputes between President Macky Sall and his opponents. These incidents are best explained as the impact of anti-French narratives designed and spread by Russia.

In countries like Mali or Burkina Faso, telling people that France no longer exploits their resources is almost impossible. Although French companies are absent from Mali and Burkina Faso’s mining sectors, misinformation persists, fueled by historical colonial grievances. This manipulation

Wagner: A Money-Making Machine

The economic model of Wagner resembles a sprawling organization that sometimes operates like a franchise. Often, the group works through a complex network of shell companies. In the Central African Republic, for instance, the official entity managing the security of local authorities is Sewa Security Services (SSS). However, intelligence reports and our sources confirm that it is, in fact, Wagner. Similarly, in Mali, the junta has officially signed an agreement with Prime Security, though this too is Wagner. This was publicly acknowledged by Yevgeny Prigozhin himself in a video shortly before his death. This strategy of concealment allows authorities, like in Mali, to continue denying Wagner’s presence on their soil. Technically, they are correct, as Wagner is not there officially. But operationally, as has been proven, Wagner operatives work under the guise of Prime Security, complete with uniforms bearing Wagner’s insignias. These operatives share their activities in Mali via Wagner’s Telegram channels and other digital platforms.

The presence of mercenaries is just one aspect of Russia’s influence war via Wagner. Another crucial dimension is information warfare. Officially registered as Concord Management, Wagner’s funding for activities in Africa is often exorbitant. To alleviate financial strain on host nations, Wagner frequently arranges to be paid by directly exploiting local natural resources.

In the Central African Republic, Wagner’s affiliates operate mining concessions under names like Lobaye Invest, Midas Resources, or Kraomita Malagasy—some of which are registered in Madagascar. Similarly, Meroe Gold, another Wagner-linked entity, operates in Sudan, the Central African Republic, and Mali. Intelligence documents reveal that mining concessions in areas such as Bria in the Haute-Kotto prefecture and Ouadda have been granted to Lobaye Invest, while Midas Resources operates in Ndassima.

In Mali, since Wagner’s arrival in 2021, the presidential budget has skyrocketed. This is largely because the Russian militia is paid from the presidency’s coffers. Reports suggest that Bamako is now struggling to meet the monthly payment of 10 billion CFA francs to Wagner, prompting the group to secure funding by exploiting gold mines in the southern regions of Sikasso and Kayes.

Russia’s Wagner model appears to be a perfect fit for neo-dictators—civilian in the Central African Republic and military in the Sahel—whom Moscow has helped gain and maintain power. Unlike Western nations, constrained by public opinion and civil society to address issues of democracy and human rights, Russia makes no such demands.

In the post-independence era, Western powers dictated and overturned regimes in Africa to suit their interests. Today, Russia seems to have taken on that role. By securing the leadership of countries where Wagner operates, Moscow has effectively turned these leaders into hostages of Putin, whether they realize it or not. Holding the reins of security, directly or indirectly, in these nations, the Kremlin now wields the power to make or break governments based on its interests.

A study from April 2024 by the Africa Center for Strategic Studies highlights the destabilizing impact of Russian influence. It notes that “disinformation campaigns aimed at manipulating African information systems have nearly quadrupled since 2022, resulting in destabilizing and anti-democratic consequences.” The report adds, “Disinformation campaigns have directly caused deadly violence, encouraged and legitimized military coups, silenced civil society members, and masked corruption and exploitation.” This underscores the threat Russia poses to Africa with its veiled colonial ambitions. Moscow appears determined to destabilize regimes unfavorable to its interests. Will it succeed? That remains the key question.

Despite nationalist and sovereignty-focused rhetoric, Russia’s resurgence in African political affairs cannot be seen as a sign of progress. The only model Russia offers its African partners is its own: absolute rule, clan-based and repressive power structures, and the monopolization of public wealth by an oligarchy tied to the state. As one African expert on governance remarked during this investigation, “Because some African leaders have flouted democracy, a significant portion of the youth in Francophone countries now dreams of an alternative system. But that alternative system is dictatorship. And Africa has already experienced that, to its great detriment.”

The truth is what it is.