Fresh Plateau killings reignite debate over selective outrage and government bias

By: Zagazola Makama

The recent killing of 25 persons and destruction of property in Jenbu Bindi, Riyom Local Government Area of Plateau State has again brought to fore the festering ethno-communal tension between herders and indigenous farming communities in the state.

As condemnations pour in from various quarters, including Plateau State Governor Caleb Mutfwang, who described the killings as acts of terrorism and genocide, it becomes imperative to objectively assess the trajectory of the crisis and the role of government in ensuring peace and justice for all, regardless of identity or ethnic background.

A deeper look into the events leading to the July 14 Jenbu Bindi attack suggests a complex and ongoing cycle of violence involving both the Fulani pastoralists and Berom farming communities. Contrary to narratives that portray only one group as victims and the other as aggressors, facts on the ground reveal a pattern of attacks and reprisals, sometimes triggered by theft, land disputes, or killings of community members.

For instance, on July 13, a day before the Jenbu Bindi incident, a Fulani herder, Usman Haruna, was declared missing after heading to tend cattle in Ganawuri. His kinsmen suspect he was killed, prompting tension. That same day, two Berom natives were killed in Torok and Gwon villages in what was alleged to be a retaliatory attack.

Even more telling is the July 10 incident in which three herders were reportedly killed and 200 cows rustled by suspected Berom militia in Fwil community. Earlier still, a Berom woman and her child were attacked on their farm by alleged Fulani gunmen in Bum village. These are just snapshots of the tragic tit-for-tat violence that has gripped Riyom and other parts of Plateau State for years.

It is on this premise that the state government’s response to the Jenbu Bindi killings must be interrogated. While the governor has been consistent in condemning attacks on Berom communities, there is often a loud silence when herders fall victim. Killings of Fulani herders, destruction of their property or rustling of their livestock rarely draw official outrage or government visits. This selective outrage only fuels perceptions of bias and deepens the trust deficit between communities and the state.

The fact remains that Plateau’s insecurity is driven by long-standing grievances between indigenous farming groups and nomadic pastoralists over land, grazing rights, and mutual suspicion. These tensions are inflamed by factors such as climate-induced migration, weapons proliferation, weak law enforcement, and lack of justice for past killings.

Describing every attack on a Berom village as genocide or ethnic cleansing without acknowledging similar attacks on Fulani settlements risks distorting the nature of the crisis and complicating conflict resolution. It also emboldens perpetrators on the other side who feel they have license to retaliate without consequence.

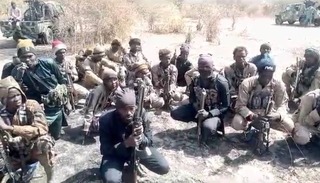

To end this cycle of violence, the Plateau State Government must adopt an even-handed approach that acknowledges all victims, regardless of ethnicity or religion. Justice must not be selective. Perpetrators from both sides must be held accountable. The calls for withdrawal of soldiers and deployment of mobile police must be guided by security intelligence and not politics, emotion or sentiments.

More importantly, the solution to the Plateau conflict lies not only in security deployments but in robust dialogue, reconciliation, and practical measures such as livestock corridors, grazing reserves, and early warning systems that address the root causes of violence.

Injustice, perceived or real is the fuel of conflict. Only by applying justice across board can Plateau truly heal. Selective empathy and lopsided condemnation only deepen wounds and entrench division.

Zagazola Makama is a Counter Insurgency Expert and Security Analyst in the Lake Chad Region