How ‘Christian genocide’ label distorts Nigeria’s conflict reality

By: Zagazola Makama

The claim that Nigeria is witnessing a state sanctioned “Christian genocide” has been trending in international discourse, amplifying domestic anxieties and sharpening an already fragile ethno-religious divide in the country.

Such narratives, when detached from the country’s complex security ecosystem, risk oversimplifying multi-layered conflicts into a single religious frame. Nigeria is constitutionally secular, and violence across its regions is driven less by faith alone than by a combustible mix of local grievances, criminal economies, identity politics, and transnational extremist agendas. When attacks occur, communities understandably interpret them through the lens of their beliefs; however, to cast the entire crisis as a binary religious war obscures root causes and hands strategic advantage to extremist groups seeking polarization.

At the psychological level, Nigerians are highly sensitive to any perceived assault on their faith. This makes the information space a contested battlefield. Episodes in Jos, Southern Kaduna, Benue and parts of Taraba illustrate how disputes over land, grazing routes, political representation and local power can quickly acquire religious colouration once violence erupts between communities with different identities.

In the Middle Belt, Nigeria’s demographic and geographic crossroads ethnicity and religion overlap in ways that allow political entrepreneurs and armed actors to weaponise narratives. What begins as a farmer–herder clash or a dispute over local authority can be reframed as a civilisational struggle, accelerating reprisals and widening the conflict footprint.

Extremist organisations operating across Africa exploit this dynamic. Al-Qaeda and Islamic State affiliates pursue parallel-state projects by stoking fear, delegitimising national institutions and provoking sectarian backlash. From the Sahel to the Horn of Africa, insurgents attack civilians, displace populations and profit from the illicit flow of small arms.

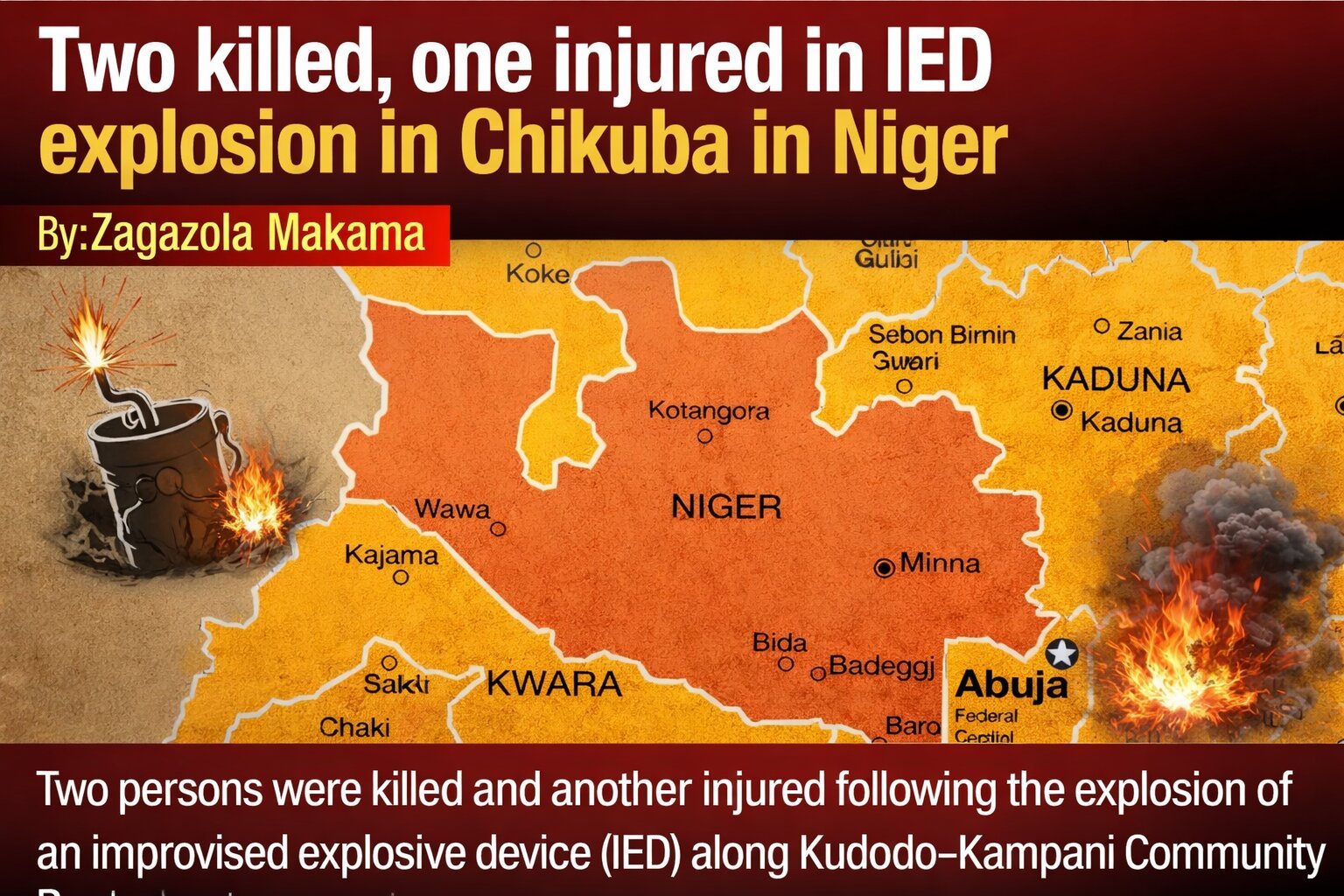

Nigeria sits at the nexus of these corridors. In the northwest and north-central zones, Boko Haram offshoots and allied cells have adapted tactics—including IED use—while cultivating relationships with bandit networks. Their objective is not only territorial control but narrative dominance: to convince populations that the state cannot protect them and that coexistence is impossible.

This is why the “genocide” label, when applied wholesale to Nigeria, is analytically flawed and strategically dangerous. It compresses diverse theatres North-East insurgency, North-West banditry, Middle Belt communal violence into a single story that misreads motive and method. It also creates perverse incentives. Extremist groups thrive on publicity and polarisation; a global narrative that frames local conflicts as a religious extermination campaign can validate their propaganda and encourage copy-cat violence. Domestically, it hardens attitudes, weakens trust in institutions, and pressures political actors into zero-sum postures rather than pragmatic problem-solving.

Psychologically and historically, Nigeria’s past from the Uthman Dan Fodio jihad of 1805 to the 1966 crisis and civil war is often misunderstood and misused. These events are sometimes portrayed as purely religious campaigns, rather than complex political and social upheavals.

Against this backdrop, the U.S.-led narrative of a “Christian genocide” is not merely an analytical error; it becomes a negative description of Nigeria as a state. It suggests official neglect or complicity and projects Nigeria as a country defined by religious war rather than governance and security challenges.

More troubling are claims that the U.S. allegedly targeted Sokoto the historical seat of the Caliphate while neglecting ISWAP/ Boko Haram in the Lake Chad and JNIM offshoots near Kainji National Park. In optics and perception, this fuels suspicion that foreign powers are pursuing broader geostrategic or economic interests rather than purely humanitarian ones.

In a country that is one of the world’s highest consumers of social media content, such narratives spread rapidly. Once the idea of “Christian genocide” takes root in the national psyche, it becomes harder to reverse and easier for extremists and political actors to exploit.

The danger is not only external pressure, but internal fragmentation. Nigeria has long faced separatist and extremist ambitions from IPOB in the South-East, to Oduduwa groups in the South-West, to ISWAP/JAS in the North-East, and identity-based movements in the Middle Belt.

When international narratives suggest Nigeria is failing as a state, they unintentionally embolden these forces. The old CIA-era projection that Nigeria would break up by 2015 did not happen but the conditions for fragmentation remain visible in elite rhetoric, online mobilisation and communal distrust.

International engagement matters, but it must be calibrated to Nigeria’s realities. Security cooperation can deliver tangible benefits counter-IED capabilities, ISR assets, air mobility and training, if anchored in Nigerian ownership and intelligence-led operations. Precision, legality and accountability are essential to avoid civilian harm and the backlash that follows.

At the same time, an exclusive focus on kinetic tools misses the wider contest. Extremist ecosystems depend on recruitment pipelines, financing, social media amplification and local grievances. Disrupting these requires governance reforms, justice for victims, and economic recovery in affected communities so that civilians have reasons to resist insurgent narratives.

The information domain is just as critical. Media must be objective at all time and not to take side. From the government side, strategic communications should be proactive, not reactive: explaining the nature of threats, acknowledging failures honestly, and demonstrating progress in protecting all citizens regardless of faith. A recent failure of Stratcom was the case of the Kaduna state government for denying abduction of 171 Christians in Kajuru and later admitted that it actually took place.

When citizens see investigations, sincerity, arrests, and prosecutions alongside relief for victims and reconstruction of communities, the space for disinformation narrows. Religious and traditional also leaders have a unique role in de-escalation, offering moral authority that counters the language of collective blame.

Finally, Nigeria’s political class must treat local crises with urgency and coherence. State governments, security agencies and community structures should align around early-warning systems, mediation mechanisms and rapid response to prevent isolated incidents from spiralling into wider conflagrations.

Federal-state coordination, coupled with border management and regional diplomacy, can limit the spillover from Sahelian conflicts. None of this denies the suffering of Christian, Muslim and traditional communities alike; rather, it insists that justice and security are indivisible.

In sum, Nigeria’s security challenge is real and severe but it is not a single-story war of religion. It is a complex struggle against transnational extremism, organised crime and politicised identity. Reducing it to “genocide” rhetoric distorts policy choices and empowers those who benefit from division. A credible path forward blends precise security operations with governance, justice and narrative resilience so that Nigerians are protected not only from bullets and bombs, but also from the ideas that seek to turn neighbours into enemies.

Zagazola Makama is a Counter Insurgency Expert and Security Analyst in the Lake Chad regio